Study Abroad Handbook

PDF version: Study Abroad Handbook

-

SECTION: I. Introduction

In 2008, the USG published the USG Handbook for Developing and Maintaining Study Abroad Programs. This handbook was focused on faculty-led programming and as the title suggests, its main focus was on development and maintenance. This handbook, published in 2019, is more general and applicable to all study abroad programs in the University System of Georgia, such as faculty-led, direct enroll, and exchange programs. This handbook is inclusive of smaller and newer institutions as well as larger and more established programs and also applies to the USG’s study abroad consortium programs.

This handbook provides a framework that presents the Board of Regents policies and procedures applicable to study abroad, discusses best practices in the field and recommends points of consideration for the development of a campus’ study abroad programming. Rather than the USG requiring a central system-level approval process for all study abroad programs, this handbook is meant to guide individual institutions which engage in study abroad activities to work with the following framework to set their own fiscal, risk management, and academic standards for their study abroad programs.

All study abroad professionals, new and seasoned, are encouraged to become familiar with the contents of this handbook and use it as an accompanying document to other established Board of Regents policies (e.g. Board of Regents Policy Manual and Business Procedures Manual). The handbook may serve as an introduction for any new employees to the USG, to the field of Study Abroad, and/or as a reference point for colleagues who interact with study abroad offices and students.

-

I.A. Study Abroad Activity

When study abroad began it was commonly called ‘Junior Year Abroad’ and was used to denote the sending of students abroad to study at an overseas institution for their third year of undergraduate studies. The field has grown and expanded, and the terminology has shifted, with some incongruence (e.g. ‘study’ abroad versus ‘education’ abroad). According to the Forum on Education Abroad’s Glossary, ‘study abroad’ is defined as a “subtype of Education Abroad that results in progress toward an academic degree at a student’s home institution” and “excludes the pursuit of a full academic degree at a foreign institution.”

In 2019, the University System of Georgia implemented a ‘Study Abroad Attribute’ in Banner, our student record system, to begin tracking coursework in which students receive credit for study abroad activities. For the purposes of this Study Abroad Attribute, we distinguish between ‘Study Abroad’ and ‘Study Away’ and have developed these working definitions:

- Study Abroad = The course is taught outside of the United States and results in the progress toward a degree at the student’s home institution.

- Study Away = The course is similar to Study Abroad and also results in the progress toward a degree at the student’s home institution but is taught within the United States in a location significantly different from the home campus.

- Faculty Led = The course is taught by a faculty member at your institution who is leading the trip.

- Branch Campus Abroad = The course is taught at a USG branch campus abroad such as the sites in Shenzhen, Metz, Cortona, Oxford, or Montepulciano.

- Embedded = The course is partially taught on the USG campus, and partially taught abroad, such as courses with a trip over Spring or Winter Break.

- USG Consortium Study Abroad = The course is taught as part of one of the USG Goes Global Study Abroad trips, such as the European Council and Asia Council trips.

- International Service Learning = Credit bearing volunteering, community development and/or other related education experience abroad.

- Internship Abroad = Credit bearing work experience abroad.

- Research Abroad = Credit bearing research experience abroad, self-organized or sponsored.

While not utilized in the Study Abroad Attribute process, we have also developed the following working definitions for other study abroad activities:- Direct Enroll (Unilateral Study Abroad) = USG student is enrolled directly at an institution abroad

- Reciprocal (Bilateral Exchange) = USG institution has a reciprocal exchange agreement in place with an institution abroad and the USG student is enrolled at the institution abroad

- Third Party Provider = USG student attends a program offered by a third party provider/company/organizer

Lastly, faculty and/or staff who are leading a study abroad trip will be referred to as Program Directors in this handbook.

-

I.B. Study Away Programs

Although domestic academic travel programs will not need to consider the specific international components of preparing for travel that are covered in the preceding sections, campuses should consider how this document could apply to elements shared between study abroad and domestic study away programs, including budgeting, academic planning, faculty training, recruitment and orientations. USG institutions should consider what kind of oversight these programs should receive and whether or not study abroad offices or other appropriate administrative offices should coordinate these activities.

-

I.C. Study Abroad Office

Consider the size of your institution and the number of students studying abroad, and how all of the study abroad programs will be managed. In larger institutions it might be prudent to outline the responsibilities of a study abroad office, separate to the responsibilities of Faculty-Led Program Directors. In smaller institutions, the faculty leading the trip may assume many, if not all of the following responsibilities:

- Program development

- Curriculum design and academic planning

- Logistical planning including registration and bursar

- Legal, budget and fiscal procedures

- Marketing and recruitment

- Student application and admissions process

- Preparing students, including information on financial aid and scholarships

- Health and safety (insurance, risk and crisis management)

- Overseas and re-entry support

Also consider who will be on campus to help prospective study abroad students and handle emergency situations if and when the main study abroad contact is leading a program abroad.

-

I.D. Institutional Study Abroad Committee

We recommend that all institutions develop an institution-specific Study Abroad Committee. All study abroad programs need to be accounted for and there should be a consistent treatment of those programs. This committee can be made up of colleagues across your campus and will be very useful in overseeing the formation of and adherence to policies, processes, program approvals and evaluations.

Consider inviting and including colleagues from the following offices on your campus:

- Study Abroad

- International Education

- International Initiatives (or any other overarching internationally focused office)

- Student Affairs/Student Life

- Individual Faculty and Staff, especially those who serve(d) as Faculty-Led Program Directors

- Legal Affairs

- Registrar

- Financial Aid

- Disability Services

- Health Services

- Security/Risk Management

- Counseling/Psychological Services

Each institution should decide how often and how (in-person, online) the committee should meet and what oversight the committee has and its overall responsibility level. Consider the following tasks the committee could do:- Review approval requests for new programs

- Evaluate existing programs

- Develop study abroad specific policies based on established institutional policies for drug/alcohol use, disciplinary infractions, etc.

- Recommend suspensions or relocations of existing programs due to changes

- Hear appeals to study abroad policy

- Establish emergency response procedures

- Develop institutional risk management policies

Note: Some institutions may decide to have an Institutional Study Abroad Committee with purview over items 1-5 above, and a separate Risk Management Committee (covering items 6-7)

-

I.E. Early Considerations

Faculty and/or academic departments that are considering the creation of a new study abroad program should understand that developing an academic experience abroad takes time and planning. Additionally, the extent to which a study abroad program holds curricular significance should be taken into account. For example, study abroad programs should be pursued if they: include graduation requirements for certain degree programs; include steps necessary to reach a mandatory practicum or capstone; address an academic gap; and/or create an academic opportunity required by a curriculum or program that is limited, or otherwise not available on campus. Innovative concepts and designs should be considered – meaning that the program recruits underrepresented students, is interdisciplinary in nature, incorporates high impact practices such as community service, internships, research, home-stays, etc. and/or travels to less common destinations. The program development process should consider:

1. Academic issues

- Why is this particular site important to students’ understanding of the subject? How would it add to students’ understanding of the subject beyond what could be achieved on campus?

- How will the course being offered enhance students’ understanding of the field?

- What will the learning outcomes be for the class?

- How will the program account for contact hours?

- How will the program fit with the departments and institutions academic objectives?

2. Feasibility & Cost

- Can the program goals be achieved at a price that is affordable for the institution’s student body? If cost is too high, students will look elsewhere or decide not to go.

- Is there sufficient time to develop the program (including site visit, budget development, academic development, etc.)? This process generally takes 6-12 months prior to recruiting student participants.

- Are there sufficient staff on campus to support the program?

- Is the program location/topic one that would appeal to students at the institution?

- Would this program duplicate other campus offerings?

- What is the Department of State’s rating of the safety of the site?

- Are there any issues with insurance coverage?

- Does the institution have enough funds to support the program fully?

Remember: Faculty who lead and/or teach on study abroad programs are performing work for those programs. As a result, they must be paid for their work just as they must be paid when they perform work on campus in the United States. Reimbursement for their work-related travel expenses, while also required, and the enjoyable benefit of going abroad are not substitutes for appropriate wages.

3. Logistics

- How will the students be transported to, from and at the site and how they will be housed and fed during the program?

- What are the programs available facilities (i.e. classroom spaces) and subject-specific resources (e.g. museums, historical sites, archives, businesses, health-care centers, media outlets, education institutions, policy or public service organizations, NGOs, performance venues, etc.)?

- What are the options in an emergency, (i.e. the location of nearby emergency facilities such as hospitals, doctors, police), how/when to contact emergency services, are services available in English, and are there any particular risks health/safety associated with the site?

- What kind of accessibility accommodations are available on site? What kind of accessibility issues might the site pose for students who require assistance?

-

I.A. Study Abroad Activity

-

SECTION: II. Program Development

Before planning a new study abroad program, please check the USG Study Abroad Directory so that we are not creating duplicate programs within the USG. In most cases, USG students from any institution can apply to another USG institution as a transient student so that s/he can attend another study abroad program hosted at a USG institution.

Smaller institutions are encouraged to utilize the USG consortium programs such as the programs offered via USG Goes Global by the European and Asia Council, to send their students abroad.

The process of developing and planning a new program takes considerable time and effort. Program development may begin with an individual faculty member or be a part of a larger department-wide discussion. Therefore, your institution may want to develop a process (and/or create an evaluation committee) that addresses the following:

-

II.A. Training for Faculty/Staff

We encourage the study abroad office (or similar) at each institution to provide informational meetings and trainings for Study Abroad Program and Faculty Directors. These meetings can provide an opportunity for discussion and consultation with various administrative offices (e.g. general counsel, counseling services, student affairs, academic affairs, disciplinary offices, student life) and promotes institutional support and collaboration in the study abroad program development process. Some topics to discuss include:

- Program director responsibilities

- Budget/finances policies

- Leading student orientations

- Handling students with disabilities, special needs, disciplinary issues

- Health/safety issues

- Disciplinary issues

- Legal liability issues (e.g. sexual harassment)

- Appropriate behavior between faculty/staff and students

- Emergency response planning

- Group dynamics

While the group is abroad, the Program Director is essentially ‘on call’ around the clock. This may seem like an exaggeration; however, Program Directors will want to keep in mind that some students who participate in study abroad programs at USG institutions have never traveled outside of the United States and possibly, outside of Georgia. Many still live in their parent’s homes. Some may have never flown on an airplane, traveled by train, or used public transportation such as buses or underground systems. There will be many situations which they will be facing for the first time in their lives, including dealing with homesickness, culture shock, and perhaps communicating in a foreign language.In order to give potential Program Directors an idea of what exactly is involved in leading a study abroad program, here is a list of potential responsibilities [Adapted from the NAFSA, Professional Development Program, Trainer Manual]:

Academic program development; Admissions and enrollment manager; Budgetary officer; Bursar; Accounts- Payable/Receivable; Compliance manager; Computer center manager; Contract developer; Course development and evaluation administrator; Crisis and emergency manager; Cross-cultural communicator and culture advocate; Cross-cultural issues consultant; Disciplinarian; Diversity and inclusion expert; Drug and alcohol counselor; Enforcer and judicial officer; Equipment manager; Event Planner; Facilities manager; Fashion police; Federal policy reporter; Health and safety officer; Housing rental agent; Currency exchange expert; Insurance agent and counselor; International communications expert; International law expert; Interpreter; On-the-spot therapist; Orientation program administrator; Parental liaison; Personal and professional counselor; Personnel manager; Program developer and evaluator; Professor; Public relations specialist; Recruiter and marketing specialist; Risk manager; Student affairs administrator; Student conduct judicial officer; Students with disabilities manager; Student health professional; Testing administrator; Textbook manager; Translator; Transportation supervisor; Travel agent and tour operator; Visa and immigration law specialist; Writer and Editor; Etc…Etc…Etc…

In particular, Program Directors should be aware of the physical manifestations of stress (headaches, gastrointestinal problems, weakened immune systems, insomnia) and prepare to help students handle the stress that accompanies change and culture shock.

A successful Program Director has the following characteristics:

- Enjoys working with students

- Possesses administrative skills

- Comfortable providing student counseling

- Comfortable taking disciplinary action and documenting

- Understands appropriate boundaries with students

- Manages situations diplomatically and can establish good relationships with institutions and other contacts abroad

- Familiarity with the host country and culture

Institutions may also consider utilizing a Program Director Responsibilities Contract which would require Faculty/Program Directors to sign a document outlining expectations and responsibilities.

-

II.B. Program Development Visits

If feasible, program development visits are an excellent way for study abroad offices and Program Directors to learn more about a specific location and will help inform many aspects of the program.

Program development visits are sometimes funded by the study abroad office, the sponsoring academic department, college, or institution more widely.

When planning a visit please consider that while it may not be possible to schedule a site visit at the same time of year as the final program would run, doing so can allow for more thorough planning as faculty/staff may get more of a feel for the facilities, campus, city, etc.

Please consider:

- Meet with appropriate faculty, student services personnel, current participants, and any third party providers you are considering

- Tour facilities (libraries, dormitories, classrooms), take note of exercise/sports, laundry and meal options and gather information about costs

- Ask about advanced fiscal planning (accommodation deposits, contracts) and negotiate costs

- Assess appropriate cultural resources (i.e. museums, NGOs, historical sites) in order to develop approaches to teaching within the space.

- Examine health, safety and security issues in the area

- Learn about local area, including local transportation and disability access

- Become familiar with local money exchange options, banking procedures

- Take note of cultural norms as related to gender, race, sexual orientation, disability access

- Develop a timetable for program implementation

- Don’t forget to take photographs and video

-

II.A. Training for Faculty/Staff

-

SECTION: III. Academic Planning

Because study abroad programs award academic credit, they must be academically substantive and the credit awarded must be in line with the standard curriculum, contact hours, and assignments. All study abroad syllabi, whether home grown faculty-led programs or coursework taken abroad at partner institutions, are required to meet SACS standards and must include a detailed course outline, learning outcomes and assessment procedures.

Remember that students will need to be informed of how to register for courses for the following term, especially if they will be abroad during this process.

-

III.A. Academic considerations for Faculty-Led Programs

1. Curriculum Design

Course plans should take advantage of the international setting while ensuring academic rigor. It is vital that instructors re-conceptualize their teaching by focusing on the development of the whole student and rooting their class in the unique experiential learning opportunities on location. The curriculum should drive the planning and the program site should enhance the courses taught and provide environmental and cultural elements.

Further, the experience on site (including any accompanying excursions) planned during the study abroad program should enhance the course(s) the students are taking and should not lead, or be the focus, when designing curriculum.

The course design should reflect the target student population’s interests and needs. Programs may employ a narrower curriculum, honed in on specific discipline or focus on a topic versus a broad curriculum that has general appeal and may recruit more students. Consider how the courses proposed will impact the curriculum of correlated academic departments. Each of these program types may have its own advantages and disadvantages, and these should be considered when determining how to market the program.

For example, the process of curriculum design may include the following points[Adapted from “Neuroscience behind Intercultural Learning” by Kartoshkina (2017)]:

- Start preparing students for cultural experiences before going abroad

- Immerse students in a variety of experiences to stimulate different parts but try not to overwhelm them

- Provide regular opportunities to help process new experiences and create shared meanings through guided discussions

- Provide time for personal reflection to strengthen newly forming connections

2. Learning Outcomes

We encourage a holistic approach. A good example of a Faculty-Led study abroad class starts with clear learning outcomes based on course structure and subject matter, and incorporates additional deliverables that can be gained from field trips and site specific activities. Class meetings should be designed to also prepare students for the site specific learning experiences beforehand and enable them to process and understand those experiences afterward. When developing learning outcomes, consider that students should be able to:

- Articulate a reasonably nuanced knowledge of the host culture and country

- Express an understanding of the student’s home culture and country identity in comparison to the host culture and country

- Understand and analyze their own developmental process as they study and learn abroad

3. Attendance, Contact Hours and Credit Earned

Usually, fewer absences (or no absences) should be allowable on short-term study abroad programs.

Study abroad is an academic experience, and each program should account for contact hours and credit appropriately. Due to the experiential nature of Faculty-Led study abroad, contact hours will include time spent directly in lecture in a classroom will be combined with hours spent engaged in field experiences, site-specific teaching and practical engagement with material. It is standard practice to reduce the number of classroom contact hours required for credit when the learning is taking place abroad, but each institution should develop some sort of minimum standard course hours based on your accreditation procedures.

Contact hours must be directly related to instructional time, docent-led visits to museums and organizations, etc. See below for guidelines on determining appropriate credit and contact hours for Faculty-Led study abroad programs:

- Standard course hours taught directly by the faculty or instructor count as 1:1

- Best practices dictate that cultural excursions and activities (including company/site visits and service learning) should count as somewhere between 2:1 and 3:1 depending on the quality/intensity of content and the qualifications of the person delivering the content. Be aware that 2:1 could be too generous and may create too much free time on an otherwise structured program.

- Time spent in transit may count if pertinent material is being covered (i.e. a guide speaking over a microphone on a bus or a faculty member leading a group discussion)

- Group meals may count when directly related to the course or the local culture

- Some best practices suggest a maximum number of contact hours per day to ensure that the students’ time is not excessively scheduled to the point of being counterproductive.

- You may also choose to limit the amount of credit allowed per length of program

For example, one USG institution uses the following guidelines:- 3 credit hour course = 37.5 contact hours

- 1 lecture hour = 1 contact hour

- 1 lab hour = 1/3 contact hours

- Field trips and field work count as labs and so 3 hours of field trip = 1 hour of contact

- 1.33 credits can be accumulated per week abroad (e.g., a 5 week program can only award up to 6 credits)

Each institution should adhere to their registrar’s policies, and/or work with their Institutional Study Abroad Committee or Curriculum Committee, if applicable, to determine how many contact hours are required to accumulate credit hours and follow institutional policies for awarding credits to degrees. It is especially important that courses offered abroad follow institutional policies or they run the risk of being considered less valuable or less rigorous. The rationale for a program’s determination of credit hours should be part of the program’s initial proposal that is approved on campus.Remember, that all study abroad courses which earn credit must adhere to SACS Academic Compliance. This means that the qualifications of all faculty must be documented with CVs including degrees and fields, teaching experience and academic posts on file. Additionally, syllabi may contain some ‘tentative’ information but at a minimum must include any prerequisites, student learning outcomes for the course, specific information on the nature and number of assignments, means of evaluation, and grading scale.

-

III.B. Credit transfer Process

Students enrolling at an institution abroad (Direct/Unilateral Exchange or Bilateral Exchange) will earn credits at this institution and then transfer these credits back to their home institution. Institutions working with international partners should decide, in advance, how these credits will transfer and how the credit will count at your institution.

Study abroad offices should provide clear information to students about the kind of credit they can receive, the process for receiving course credit and how credit earned affects (or doesn’t affect) Financial Aid. Below are suggestions for keeping track of this information:

Create a plan of study via a Study Abroad Credit Approval Form (or process)

- This will confirm for students that they will receive credit for courses taken abroad, prior to departure

- It will be essential for study abroad advisors, academic advisors, and Financial Aid to all be on the same page

Create a mechanism for students to verify their courses once they are on site through a Verification of Enrollment Abroad Form (or process)

- This will ensure that students are correctly registered and therefore ‘making satisfactory progress’ towards degree completion

- It will provide a mechanism for recording course changes and assessing appropriate credits

- It can assist with attendance verification for Financial Aid purposes

- This will also inform study abroad advisors(or similar) if students have enrolled in a different number of course hours or in different courses than were originally indicated on the Study Abroad Credit Approval Form and adjustments can be made as necessary

-

III.C. Grades

Institutions should consider the time it takes for grades to come back to the home institution. This ‘lag time’ can occur with Direct/Unilateral and Bilateral exchanges, Third Party provider programs, consortium programs, etc. and will vary by the time of year and by the host country or institution abroad. The USG recommends that students are informed of typical timelines and expectations should be set for receiving final transcripts from host institutions, allowing students to make informed decisions when choosing a program. Study abroad offices are encouraged to work with colleagues across campus to diminish any hindrance on the students’ ability to:

- Receive appropriate and timely Financial Aid

- Pursue graduation, or

- Register for classes

Also, institutions should consider how grades earned abroad will be translated back home. Courses taught by the home institution’s faculty, or on a branch campus, or via on the USG consortium programs are straightforward and count directly on the student’s transcript/record. However, credits earned via Direct/Unilateral exchange, Bilateral exchange or Third Party Providers may be demonstrated on the student’s transcript as:- Credits earned only

- Pass/Fail

- Converted directly into U.S. grades and listed on the transcript

- Factored into the student’s overall GPA/or not factored into the institution’s GPA

If students are studying at an institution that does not use the same grading system employed in the U.S., study abroad offices should provide them with information about appropriate equivalents, both to help students gauge their progress while overseas and to help students understand their transcripts at the end of the term.

-

III.A. Academic considerations for Faculty-Led Programs

-

SECTION: IV. Logistics

-

IV.E. Mixing with the Local Culture

One of the most rewarding experiences for participants of study abroad programs is getting to know the host culture, and program planning should include consideration of and logistical planning for activities that will allow students to engage with that culture in meaningful ways. Here are some examples of how to incorporate these experiences into your Faculty-Led study abroad programs:

- Invite local students to participate in your program in some way

- Introduce collaborative projects between your students and the local students abroad

- Coordinate field trips and excursions with local students

- Attend local festivals, ceremonies, events, plays, etc.

- Invite local speakers to give guest lectures

- Set up language partnerships between your students and the local students abroad

-

IV.A. Proposals and Approval

Each institution should develop a process to help guide the development of programs, approve new programs, and evaluate programs that will continue. As discussed above, the recommendation from the USG International Education office is to assemble an Institutional Study Abroad Committee who will help guide the institution towards a decision about your approval process for new and continued programs.

For reference, Section 21 Study Abroad Programs of the USG Business Procedures Manual stipulates that all new/inaugural programs must be approved “by the president of the institution, or his/her designee, under the authority delegated to the president by the Chancellor.” Further, there must be an annual review of all programs and “institutions must conduct a review of all returning study abroad programs.”

The establishment of an Institutional Study Abroad Committee will help each institution institute a process in which new and continuing study abroad program offerings are reviewed. You might consider the following:

- Timeline for receiving and reviewing proposals (e.g. annually, bi-annually, rolling basis)

- Type of proposal for different study abroad activity (e.g. You may have a different proposal for Faculty-Led programs, than for proposing an international partner to establish bilateral exchange)

- Level of authority (e.g. Who will you require to sign-off - Senior International Officer? Deans? Department Chairs? Business Managers?)

- Documents you may require:

- Program budget template

- Timetable for program implementation (including payment deadlines, and cancellation/refund policies)

- Learning outcomes, draft syllabi

- Proposed itinerary and official program operating dates

- Proposed faculty/staff +Emergency response plan, including 24/7 emergency contacts who will accompany programs

- Contingency plans - identify faculty/staff as back up in case program leader becomes incapacitated

- References, if any Third Party Providers are being used

- Program development visit report (if applicable)

-

IV.B. Accommodation

Types of accommodation include on-campus/partner university dormitories (single, shared, suites with shared living areas), hotels, hostels, guest houses, apartments or homestays. Securing accommodation may be one of the first tasks in planning for a study abroad program as some dormitories, for example, may require deposits 8 months to a year in advance.

When choosing the type of accommodation(s), consider the following:

- Expense

- Facility itself

- Cleanliness and overall maintenance.

- Security of facility and evacuation routes - fire/emergency exits.

- Will your students need to share a room, or will they have their own?

- Laundry?

- Internet Access?

- In more extreme temperatures, is there A/C,fans and heating?

- Location/local Area

- Safe neighborhood?

- Close to education facilities?

- Ease of local transportation?

- Do you have students with special arrangement needs? (e.g. disability access)

- Integration with local culture

- How will your students integrate (or not) with local students?

- What exposure will your students have to local people/families? Local language/customs?

- How will your students eat? Self-catering vs. meal plans

- How much time is needed to arrange? Hotels are quick and easy, but homestays require much more time

- Where will participating faculty and staff be housed in relation to the students?

- If using host families or homestays, ensure that the families have gone through an adequate screening process and have been properly vetted

- How will you assign/place students? Consider using a preference questionnaire but keep in mind that offering ‘too much’ choice will make the program more difficult to plan

- Is there a procedure for addressing complaints?

Accommodation evaluations are a useful tool in helping the Program Director/study abroad office determine if there are any problems that should be resolved.

-

IV.C. Group Travel Arrangements

When planning for Faculty-Led programs, some institutions may decide that they prefer faculty and students to travel together, ensuring that all participants arrive at the site at the same time. However, some institutions may decide to plan for students and faculty to meet at the site.

If participants will travel together, you may be able to secure a group rate for airline tickets when you have 10 or more participants. Group tickets may also make arranging airport pick-ups easier to facilitate. Please keep in mind that securing a group rate will require advance planning, since seats will need to be reserved 6-10 months in advance and secured with a deposit.

However, group flight purchases are not always the cheapest option, and involves more work and coordination on the part of the study abroad office and/or Program Directors. Keep in mind that some students may request to fly separately from the group using frequent flier miles or ‘buddy passes.’ Others may wish to travel on their own before or after the program. These options can be cheaper and offer flexibility for the students but we would caution against students relying on utilizing a standby seat to travel to the program, as their delay could cause disruption to the other participating students and/or the faculty.

If purchasing group tickets, consider the following:

- What is the minimum number of tickets that need to be purchased for the group rate to apply? What happens if you fall short?

- What taxes and fees are included in the price?

- Is there a cancellation policy, and what is the penalty for changes and cancellations?

- What is the deposit due date for the tickets, and when is the final payment deadline?

- When is the final list of group flight names due to the airline?

- Inquire if the travel agent can also help process visas for the group (if applicable).

- Is it possible for a student to alter their arrival/departure date and if so, how is this done?

You may also want to look at other group ticket options to keep costs down. Group meals, train tickets, museum/exhibit admissions, etc. are good options to pursue. Keep in mind that some have minimum and maximum number requirements, reduced rates may require proof of student/educator status, required tour guides, wardrobe requirements, and tight reservation schedules.Student-focused travel organizations or Third Party Providers may provide ease for making group arrangements as they cater to travel for study abroad groups.

-

IV.D. Meal Planning

Meals should take advantage of the host country culture as much as possible while taking into account the program structure and budget. Ideally, there should be a balance between quality, authenticity, affordability and convenience.

Programs may include some, all, or no meals in the fee they charge students, but all programs must determine how students will have access to dining services or cooking facilities during their time abroad and must inform students of these options.

Consider students with special dietary needs, if your accommodation facility provides any meals and how faculty/staff meals will be purchased.

-

IV.E. Mixing with the Local Culture

-

SECTION: V. Legal Issues

-

V.A. Executing Contracts

Regardless of the type of contract (accommodation, group museum purchase, group meal, etc.) there should be some sort of written document between the USG institution and the provider.

- Advance purchasing is recommended wherever possible

- If you can arrange to pay in U.S. dollars (rather than the foreign currency) this could be beneficial as it would avoid the possibility of fluctuating exchange rates

- You may choose to contract with a local organizations to help secure housing, tours, etc. but keep in mind that this may raise the cost

All study abroad offices/Program Directors should liaise with the necessary on-campus offices (e.g. Purchasing, Legal) before signing any contracts. Any contract with a foreign institution, the owner of a property abroad, or a travel provider should be sent to Legal Affairs for review and signed by the appropriate designee authorized to sign such agreements. Keep in mind, you may not be allowed to sign contracts! Some campuses have very strict policies about who is authorized to sign.

-

V.B. EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect on May 25, 2018 and is designed to:

- Harmonize data privacy laws across Europe

- Protect and empower all EU citizens’ data privacy, and

- Reshape the way organizations across the region approach data privacy

EU GDPR protects ‘natural persons’ personal data processing and the free movement of their personal data. For U.S. academic institutions, ‘natural persons’ include: students (attending study abroad programs in the EU), faculty (hired locally or posted to the EU), staff and other personnel (hired locally or posted to the EU) and third parties in general (i.e. EU contractors, EU donors, EU researchers).Further information about EU GDPR can be found on American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO)’s compliance website. The USG has provided further information about EU GDPR on the Data Privacy Policy and Legal Notice website. USG institutions are required to work with their Legal teams to maintain compliance with EU GDPR regulations.

-

V.C. Clery

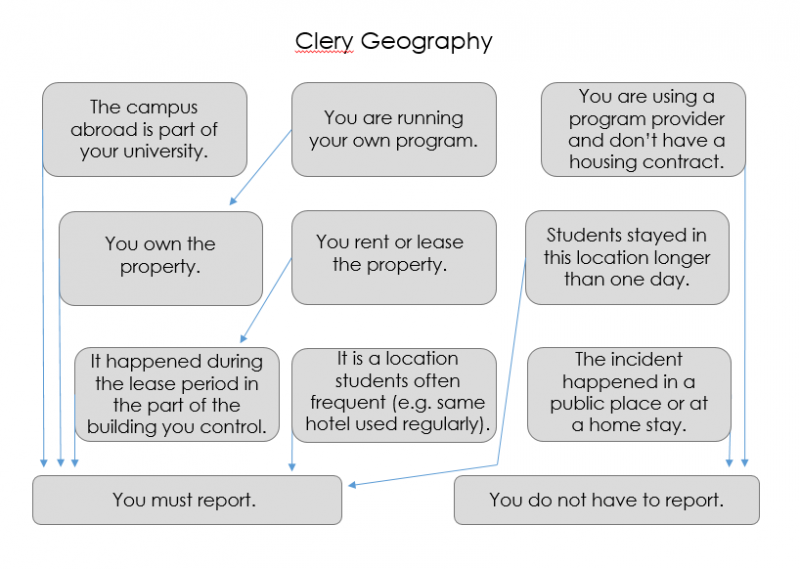

Signed into law in 1990, the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act is monitored by the Department of Education and dictates mandatory requirements to include an annual report, crime log, timely warnings and emergency notifications, and crime statistics.

The following graphic[Adapted from NAFSA e-Learning Express: Essential Federal Regulations for Education Abroad ] is useful in explaining the geography around Clery and reporting:

-

V.D. Title IX

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs and activities that receive federal funding. Title IX provides that:

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Title IX prohibits discrimination in any university program including athletics, admissions, academic programs, extracurricular activities, employment, financial aid, housing, and student services. Title IX prohibits discrimination by and against both males and females, by students, faculty and staff.

-

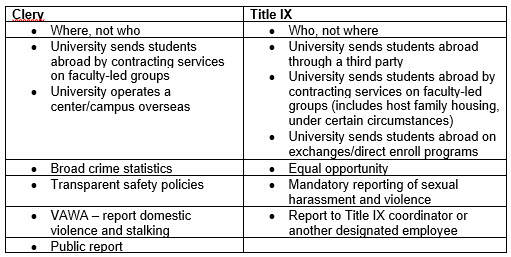

V.E. Clery vs. Title IX

It is important that all colleagues that work with study abroad processes, as well as all students, understand their responsibilities under the Clery Act and Title IX. Each institution that supports study abroad programming must provide resources and training to assist study abroad faculty in navigating their roles under these federal statutes.

Both Clery and Title IX covers a basic principle that a duty of care should be in place for all students at all times and in all places. The following description[Adapted from both 2015 NAFSA Annual conference presentation: “Promoting Security Abroad: Analyzing Title IX and VAWA” and NAFSA e-Learning: Essential Federal Regulations for Education Abroad] of the differences in emphases between Clery and Title IX may be useful:

-

V.A. Executing Contracts

-

SECTION: VI. Budget & Fiscal Procedures

A key element of study abroad programming is making sure that there is enough money in the program budget to pay for all program costs and that the management of funds follows federal, state, and institutional guidelines. If the study abroad program is ‘homegrown’ (e.g. Faculty-Led) then the study abroad office/Program Director has financial responsibilities.

Sound budgeting will serve you well in avoiding funding shortages and to keep student costs down. Once announced, student costs should not be increased as that will lead some students to withdraw and could draw question to the program’s integrity.

See Section 21 Study Abroad Programs of the USG Business Procedures Manual for full details on the Fiscal Procedures involved with study abroad programming.

-

VI.A. Budget Template

It is recommended that campuses set one standard budget template for all of your study abroad programs, but may develop a few templates if the campus supports programs that require different budget models.

The budget template should include:

- Transportation

- Airfare – Note: Some offices may decide to include airfare costs during the trip (e.g. in-country flights), but not international airfare to/from the start and end of the program. This is up to each individual institution to decide, and we recommend that you review the aforementioned ‘Group Travel’ section for further discussion.

- Transportation to/from airport in country

- Housing/lodging facilities

- Meals (the number of meals included may vary, depending on the program’s accommodation plan)

- Insurance (accident, sickness, trip cancellation); see information later in this handbook about the CISI Insurance Plan for study abroad groups

- Instructional expenditures (e.g. rooms/equipment for instruction/administration

- Admission per person for museums, cultural events and other program activities

- Cost for purchase of local phone or phone service to assist with emergencies on-site

- Excursions (and associated travel expenses)

- Fees for guest lectures, guides, etc.

- Travel expenses & meal allowances for faculty/staff

- Overhead costs

- Funds to build the ‘Emergency Fund Reserve’ until the chosen percentage is reached

- Advertising to recruit students

- Transportation

-

VI.B. Program Charge

First, determine a target enrollment number for which you will budget based on an estimate of student interest and the program’s capacity. Best practice in the field points to student faculty ratios between 15:1 and 10:1.

Then, to determine the students Program Charge, you would add up all of the program’s expenses and divide the sum by the number of paying participants required to break even. This basic calculation indicates that if you recruit more students and the program has a surplus, then the excess money is refunded back to the students. And, if you recruit less than your ‘break even target’ then the program may need to be canceled, or the sponsoring department/institution may need to cover the amount of shortfall. Setting the Program Charge amount needs to follow institutional, USG and state-legislated policies. Also, we encourage programs to prioritize student affordability.

There may be additional costs, outside of the Program Charge. Each institution should determine which expenses are included, and which are not included in the Program Charge.

Examples of costs beyond those usually included in the Program Charge (though this may vary by institution) are:

- International airfare (see note above)

- Passport/visa fees

- Meals not included in the program

- Ground/local transportation

- Optional excursions

- Costs associated with communication (personal phone use, internet access)

- Library/student facility fees (if offered by the host institution)

- Insurance beyond the standard program insurance

- Books/supplies

- Medical exams, vaccinations

Students should not be asked to pay extra for required program activities once on-site. They should be made aware of estimated costs for optional excursions or activities and those that can be paid out-of-pocket on top of the program fee.Study abroad offices should work with their campus financial offices to determine the best method (e.g. check, money order, debit card or credit card) of collecting the Program Charge for their institution’s programs from students. Study abroad payments can be divided into installments to allow for as much flexibility for the student as possible, as long as students understand that each payment needs to come in by a certain deadline.

-

VI.C. Accounting

Study abroad programs should work with your business office(s) to establish:

- Which types of accounts should be used for which types of funds

- How to appropriately report travel expenditures

- Considerations regarding payroll, benefits, related taxes for faculty/staff employed by the study abroad program. Compensation should be legal and fair and meet the academic unit’s approval. There is no set process for paying a faculty member - some programs pay a flat fee, while others pay faculty a percentage of their salary.

-

VI.D. Timelines

Each institution should determine payment schedules that align with payment deadlines to ensure that all program fees and tuition have been collected early enough to facilitate making timely deposits and adhere to realistic installment plans to pay vendors.

The USG recommends that all study abroad programs reconcile their budgets within a reasonable amount of time from the end of the program, but no later than six months from the end of the program.

-

VI.E. Fiscal Policies

Also, you may consider developing written policies regarding the following:

- Cancellations and refunds including:

- Student cancellation

- Program cancellation

- Cancellation of certain program elements

- Note: refund policies should address issues of illness, financial hardship, academic ineligibility, host country instability

- Deposits, defaults and/or damages. For example, many institutions will prevent a student from registering or receiving transcripts for non-payment of institutional debts

- How funds will be managed while abroad

- How petty cash will be managed. For example, it is best to try and pay for as much as possible in advance to avoid the risk of carrying large amounts of money abroad.

- How to maintain appropriate fiscal records involving currency conversion transactions

- Cancellations and refunds including:

-

VI.F. Study Abroad Tuition

Students pay their tuition for study abroad the same way they pay for non-study abroad credit. Consider your institution’s fee plan for students participating in summer study abroad programs and which fees students are charged, and which fees they are not charged. (e.g. Technology Fee, etc.)

The USG Board of Regents Policy Manual allows for out-of-state students participating in USG study abroad programs to be assessed in-state tuition. The relevant provision [7.3.4.1 Out-of-State Tuition Waivers] is as follows:

An institution may award out-of-state tuition differential waivers and assess in-state tuition for certain non-Georgia residents under the conditions listed below. [Reciprocal: 3] Any student who enrolls in a USG study-abroad program to include programs outside the State of Georgia but within the United States and study abroad programs outside the United States. Tuition and fees charged study abroad students shall be consistent with the procedures established in the USG Business Procedures Manual and as determined by the institution president.

-

VI.A. Budget Template

-

SECTION: VII. Technology, Data & Social Media

-

VII.A.Student Application Management Systems

If feasible, the USG recommends that institutions consider a student application management system. These can be useful for program planning, student applications – both for programs and for scholarships - and some are set-up to additionally serve as a CRM (customer relationship management) tool which can contribute to the growth of study abroad numbers. USG institutions work with organizations such as Terra Dotta and Via TRM.

-

VII.B. Safety Management

There are additional software and application programs available that focus on traveler safety. USG institutions work with Keynect Up – which acts as a contact card so that students always have access to important contacts, whether they have access to the internet or not. USG institutions also work with AlertTraveler – which is used for risk management purposes as it will ‘ping’ all students who are in a particular location and the students can respond, so administrators know they are okay by clicking a button.

-

VII.C. Data Reporting

All USG institutions are expected to complete the Institute for International Education’s Open Doors data submission for Study Abroad each year. If your institutions’ numbers include less than 10 study abroad students, you should also report these figures directly to the USG International Education office.

-

VII.D. Social Media

Social Media is a useful tool in connecting with prospective, current and alumni study abroad students. Study abroad offices utilize an array of programs (Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, LinkedIn and/or a blog) to advertise study abroad programs and events, increase study abroad participation, provide a learning platform, connect with students and attract donors. Social media programs are also used to advertise deadlines; share scholarship information; introduce staff and student workers; post photos of the day from a photo contest; connect with other offices and departments on campus and remind students of advising hours.

-

VII.A.Student Application Management Systems

-

SECTION: VIII. Marketing & Recruitment

Marketing and recruitment efforts should be considered, especially in order to reach enrollment goals. Successful marketing needs to extend beyond providing brochures and putting up a few posters. Recruitment activities should be coordinated amongst the study abroad office and involved staff and faculty and all should be actively involved in reaching out to students who might benefit from participating in the program

Consider where you might reach the kind of student who will benefit from your program: are you looking for students in a particular major or who haveve completed a particular set of academic requirements? Are you looking for students who are working on introductory requirements? Then consider ways that you can meet these students where they are to get information out to them about the benefits of study abroad and of your program in particular.

Recruitment tactics you may consider:

- Study abroad fairs: Plan your own fair and/or attend others

- Specific advising sessions: Some institutions utilize peer-to-peer advising, hold 101 sessions regularly, have ‘walk-in’ hours or use an appointment system

- Web presence: Website, social media

- Upload your programs annually into the USG Study Abroad Directory

- Brochures/Posters/Fliers/Digital Marquees around campus: Highly trafficked buildings, residence halls, campus buses

- Use alumni/returnee SA students wherever possible

- Assist returned study abroad students in forming a club to help get the word out

- Use academic departments and faculty to recruit:

- Relevant departments should be targeted;

- Involve active faculty and ask them to distribute program material, approach students who might be particularly suited, allow for short presentations to be made during class

- Work with the office that plans New Student orientations to capture students’ interest early (both Freshman orientation and also during Transfer Student orientations)

- Forge alliances with campus administrators (minority students, LGBTQIA, disability services, commuter student services, etc.) and plan co-recruitment events and specific information sessions (e.g. Black History Month, Science Fairs, etc.)

- Partner with relevant student organizations to identify/target any relevant student groups

- Sororities/fraternities

- Internationally-focused clubs

- Minority organizations

- Organizations for disabled students

- Commuter student organizations

- Academic/honor societies

- Don’t overlook students’ support network and the effect of their opinions (e.g. parents, spouses, significant family members) but keep FERPA regulations in mind

- Set aside funds in your budget for recruitment, marketing, and travel, if necessary

- Lastly, consider what will happen if your enrollment target isn’t met and define your threshold for cancellation

-

VIII.A. Underrepresented students

When preparing a marketing and recruitment plan, consider how you can successfully target underrepresented students in study abroad, which include:

- Racial & ethnic minorities

- Males

- Non-traditional aged students (e.g. over 26)

- Freshman or sophomore level students

- Two-year college students

- LGBTQIA students

- Students in majors outside the social sciences/humanities

- Disabled

- Veterans

- Athletes

In order to successfully ‘target’ underrepresented students, specific strategies should be used and you will need to consider the current practices at your institution (e.g. policies, communication, processes and programs) and work through how and if these could be altered so that underrepresented students can become better represented.Using disability and accessibility as an example of an underrepresented student, consider the current practices at your institution using the following questions[From NAFSA 2018 Annual Conference Presentation: “Expanding Access and Support for Education Abroad Students with Disabilities”]:

- Policies:

- Do you currently have any prohibitive policies in place? How might you be able to modify any existing policies to make them more accessible?

- Communication:

- How could you make your communications more inclusive? How could you enhance your marketing and outreach to students with disabilities?

- Processes:

- How do you address overseas accommodations during student advising? How can you better train yourself and your staff to work with students with disabilities?

- Programs:

- What is your current practice for reviewing program details to ensure accessibility? What are some reasonable steps you can take to make one/some/all of your programs more inclusive?

1. Students with Disabilities

Following the previous example, there are several steps study abroad offices may take to ensure that students disclose early so that accommodation needs can be identified and that study abroad professionals are equipped with the necessary resources and tools to advise students with disabilities [From September/October 2007 International Educator: “Students with Disabilities Self-Study for Advisers”]:

- Develop office procedures on how to advise a student with a disability and train all staff

- Create a handout to have in your office and on your website with specific steps students with disabilities should take to identify a program and assess accommodation possibilities

- Include wording in your promotional materials that invites students with disabilities to disclose their interest early, and provide space in your application for disclosure

- Develop linkages with appropriate colleagues in your disability services office

- Include information about your own program locations, as well as other partners, on the procedures in place to assist students with disabilities

-

VIII.B. Program Viability

If a program does not recruit sufficient students and does not have enough funding to provide the experience for the number of students who have signed up, the program will need to be cancelled. Campuses should determine a means for assessing the viability of approved programs, taking into consideration the recruitment cycle, the program’s initial budget, other possible funding available to support the program and related factors. Decisions about viability should ideally be made at least 3 months prior to departure. Depending on your institutional policy, programs that are cancelled may need to refund monies paid by students, and this factor needs to be taken into consideration in determining a timeline for assessing program viability.

-

SECTION: IX. Financial Resources for Students

Many students will perceive study abroad as out of their financial reach, and so it is important for study abroad offices and Program Directors to provide students with information that can help them understand their financial options. This information can help campuses increase access across the USG.

-

IX.A. Financial Aid

Financial aid is a critical issue for students wishing to study abroad. In short, federal and state financial aid is disbursed to student accounts and excess money is refunded to the student, just as if the student were studying on campus. An institution can award Financial Aid if the home institution awards credit, and if the student remains concurrently enrolled. In order to receive any Financial Aid, the student must be achieving ‘satisfactory progress’ but the definition of this may vary from institution to institution. Also, the credits earned abroad don’t need to count directly into the students’ GPA but the actual grades earned abroad need to be reported to the Financial Aid office as it must be determined that the student is making ‘satisfactory progress’, which is sometimes abbreviated as ‘SAP’.

Study abroad offices should inform students upfront about programs that are not approved for Financial Aid. Sometimes this depends on whether or not the program is ‘sponsored’ by the home institution or if the student becomes a ‘transfer’ student for the purposes of the program. The USG recommends that, where possible, study abroad programs are set-up so that students may use their Financial Aid.

Keep in mind when financial aid money is disbursed and by what method, and how this can be affected by external deadlines. As permitted by federal laws/regulations, Financial Aid offices have discretion in awarding based on the estimated cost of attending the home institution, or based on the estimated cost of attending the study abroad program overseas (assuming this cost is higher). The COA or ‘Cost of Attendance’ is defined as being a ‘reasonable’ and good estimate of actually attending the institution in question, and may include items that are required of the program, such as airfare, immunizations, passports, visas, etc.

Study abroad offices should know what students need in order to apply for Financial Aid (e.g. an acceptance letter that may require certain information - name, student ID, hours of enrolment, enrolment status, etc.)

If the student is participating in a non-home institution program, both the study abroad and Financial Aid office need a written release from the student before providing information to any third party (e.g. FERPA)

It is important that the study abroad office works towards building and maintaining a positive relationship with the Financial Aid office, Bursar’s office, Student Loans Office, etc. The goal is for study abroad professionals to have a thorough understanding of how processes work so that the burden on students is lessened. Some best practices that USG institutions have shared [Compiled from the October 2018 Study Abroad and Financial Aid Workshop hosted by the USG International Education office] to maintain positive relationships between study abroad and Financial Aid are as follows:

- Personally meet your colleagues, hold regular meetings and trainings and consider a Study Abroad & Financial Aid Advisory Council, or similar.

- Establish a study abroad point person(s) for the Financial Aid office, and vice versa

- Work towards using, and at least understanding each other’s terminology

- Collaborate and attend each other’s events (e.g. Financial Aid representation at Study Abroad Fairs)

- Utilize shared drive space to share budgets, enrollments, calculating and awarding scholarships

- Map out when aid is disbursed, deposit and payment schedules, etc.

- Co-develop written policies and procedures

- Share study abroad enrollments, as well as Financial Aid recipients, so that the study abroad office can encourage scholarship applications (e.g. Gilman) from these students

- Require that all study abroad students personally go to the Financial Aid office as part of their application to study abroad

- Utilize a Verification Enrollment Form which requires signature(s) and if the student accrues more or less hours then the Financial Aid can be adjusted

1. HOPE and Zell

Georgia’s HOPE Scholarship is available to Georgia residents who have demonstrated academic achievement. The scholarship provides money to assist students with the educational costs of attending a HOPE eligible postsecondary institution. Georgia’s Zell Miller Scholarship is available to Georgia residents who have demonstrated academic achievement. The scholarship provides money to assist students with the educational costs of attending a Zell Miller Scholarship eligible college.

HOPE and Zell funds can be utilized for study abroad as long as the home institution accepts the credits earned and the amount paid is the same as what the student would have received if they would have been at the home institution. Whichever Georgia institution awards the transcript is also the institution that disburses HOPE/Zell. For example, if a UGA student attends a UNG program, UNG needs to complete the HOPE transient form so that the UGA knows that UNG will be providing HOPE/Zell for the associated courses. If another U.S. institution is ‘hosting’ the program, then the home institution pays the HOPE. Please note that ‘Study Away’ is the term used by HOPE and Zell to refer to study abroad programs.

-

IX.B. Scholarships

A handful of USG institutions have been approved for an International Education fee and make use of these funds for student scholarships. Other institutions may consider establishing an institution-specific study abroad scholarship on your campus. You may start by contacting your Development/Alumni offices, as they can identify the best possible funding sources and assist you in coordinating your fundraising efforts.

Some government agencies, private foundations, and other external organizations offer scholarships but more often these are for semester or year-long study abroad. For example, the U.S. Department of State’s Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship is a grant program that enables students of limited financial means to study or intern abroad. The program has been successful in supporting students who have been historically underrepresented in education abroad, including but not limited to:

- First-generation college students

- Students in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields

- Ethnic minority students

- Students with disabilities

- Students attending HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) or other minority-serving institutions

- Students attending community colleges, and

- Students coming from U.S. states with less study abroad participation

If your institution/department has scholarships to award make sure there is a committee and set process in place to document everything to ensure transparency with students. Also, it is important to work with the Financial Aid office for disbursement, if necessary.

-

IX.A. Financial Aid

-

SECTION: X. Application Process

-

X.A. Student Application

When determining your student application process, focus on transparency and ease of submitting the necessary information. Consider what information you need from the student initially, and don’t collect information you will not use. For example, do you need and will you use a students’ U.S. phone number and local U.S. address, or their permanent address? We recommend that all institutions consider the most effective way to deal with students’ data when creating an application system. The USG recommends the use of software and an online platform to collect application information. Ideally your software should be integrated with Banner.

Information you might want to collect in the application phase:

- Full name

- Contact email

- Date of birth

- Academic level

- Major

- Student ID

- Emergency contact info

- Term applicant applying for

- Any questions pertaining to disciplinary records, mental or physical health, access and ability

- Financial Aid status

You may consider:- Using an administrative/application fee to support office initiatives

- Asking students about passports, so that you can identify students without passports early

- Asking students to agree to be contacted in the future as a program alumni

- Asking how the applicant learned about the program, to help you better target recruitment efforts later

- Asking for any information that you will later need to compile institutional, USG, or national reports (e.g. Open Doors)

The USG recommends that all study abroad offices work with the appropriate offices on their campus - Legal, Registrar, Information Technology, Procurement, Security, etc. to understand when it is permissible to collect certain data and the appropriate permissions needed to use that information and to develop a plan to collect waivers, signatures, or other student information deemed necessary, such as:- Acknowledgement that students are aware of financial and personal responsibilities

- Students agreement to abide by the program’s rules and codes of conduct

- Health/Medical information (allows students the opportunity to disclose medical conditions, concerns, needs)

- Emergency medical care/authorization

- Release and waiver of liability

- Assumption of risk

- Covenant not to sue

- Statement of responsibility

- Title IX reporting

- Clery Act waiver

- EU General Data Protection Regulations

- FERPA release to give student information to parents, host institutions and Third-Party providers (if necessary)

1. Medical Disclosures

USG institutions should work with their Institutional Study Abroad Committee and, in particular, their legal team, to set a policy and practice around study abroad students and medical disclosures. It is understood that students not disclosing medication or medical issues has the potential to cause problems. Some institutions have adopted a type of don’t ask, don’t tell approach for liability reasons, whereas others have required a medical doctor to sign-off on the health clearance form.

2. Liability

In study abroad, the most common example of negligence is a failure to counsel students sufficiently about risks and dangers—natural, social, political, cultural, and legal—inherent in living in a foreign environment. Also, other forms of liability stem from not providing the services or quality of services promised.

It is important to emphasize that the standard of care in study abroad programs is higher than at the home campus because students are in unfamiliar environments without the support networks to which they are accustomed. In addition, students may be operating in non-English speaking populations.

We encourage USG institutions to be conscious of these facts during pre-departure preparations and on-site management of the program. USG institutions should consider working with their Study Abroad Committee, in particular, their legal team/counsel to develop language around liability and/or liability waivers. Specifically, USG institutions may consider the following:

- Changes in travel plans and/or program attendance made by applicant for any reason including but not limited to personal emergencies.

- The acts and/or omissions of any common carrier, airline, railroad, motor coach or bus company, hotel, restaurant, tour guide, act of God, natural disaster, pandemic, war, armed conflict, or terrorist action.

- Changes in international exchange rates.

- Changes in fees, rates, and tariffs of any third party contracting to supply goods or services to the institution for the program.

- Changes in schedule due to the acts or omissions, including the withdrawal of any hosts, or program participant, or due to any other cause.

You may also choose to consider a ‘force majeure’ clause that explicitly states what actions may be taken in times of global pandemic (or other emergencies).

-

X.B. Evaluation

Institutions should decide who will evaluate study abroad applications and how much time is needed. You may choose a specific deadline for all programs, varying deadlines depending on the program, or a ‘rolling admissions’ process.

If the program is a Faculty-Led program, you may decide to involve the Program Director(s). If the program takes place at another institution (e.g. Direct Enroll or Exchange), you should keep in mind that institutions abroad may have their own application procedures and criteria.

In general, study abroad students should be in good academic and disciplinary standing, must maintain appropriate standards of behavior and meet any course prerequisites to be eligible to apply.

Individual programs may determine higher requirements for GPA or other qualifications for entry (such as minimum language proficiency), based on the program content. Study abroad programs may request other materials to assess eligibility for admission, such as a personal statement or essay or letter(s) of reference.

Your Institutional Study Abroad Committee may consider asking students for the following documentation for evaluation:

- GPA (official or unofficial transcript)

- Personal statement or essay

- Foreign language skills (if necessary)

- Students’ academic standing, and if any pre-requisite courses are required

- Reference letters

You may consider sending an ‘applied for study abroad’ student list to your Dean of Students (or similar) since certain discipline issues may need to be reviewed before students are admitted to a program.As a reminder, the American with Disabilities Act calls for reasonable accommodation to enable a disabled person to accomplish the same task as a non-disabled person. However, as foreign entities cannot be compelled to provide access based on U.S. law, it is important that each institution work with your legal counsel and office of disability services for any students requesting accommodations.

-

X.C. Special Cases

1. International Students

You should consider the effect of international students’ participation on your programs and how this may affect their visa status. Also, sometimes international students wish to participate in a study abroad program in their home country and the study abroad office (or similar) should discuss if this is allowed at your institution.

2. Minors (18 years or younger)

Most institutions require that study abroad student participants are at least 18 years of age in order to participate in study abroad. This issue comes up if/when a Dual Enrollment student inquires about participating in a study abroad course/program. The USG Student Affairs Policies and Resources document includes a section on Dual Enrollment FAQs, copied here:

Question: Can Dual Enrollment students participate in USG study abroad programs?

Answer: Dual Enrollment students wishing to participate in USG study abroad programs must first review the study abroad policies in place at the postsecondary institution offering the study abroad program. The majority of USG institutions do not allow students under the age of 18 (defined as Minors hereafter) to participate in study abroad programs.

If the USG institution offering the preferred study abroad program does not have a policy preventing students under the age of 18 to participate then the USG institution should consider the following issues before allowing a minor to participate in a study abroad program:1. Parental Consent Due to increasing instances of child abduction in custody cases, human trafficking and other illegal activities involving minors, an immigration officer, airline, travel agent or other official may request or require documentation of parental consent if a child is traveling internationally with another adult who is not the minor’s parent/legal guardian.

A sample letter of consent to travel is available on the U.S. Department of State’s website. It is best practice to have the letter of consent signed by both parents and notarized. If there is no second parent with legal claims to the child (e.g., deceased or sole custody), any other relevant paperwork, such as a court decision, birth certificate naming only one parent, death certificate of the second parent, etc., can replace the letter from the second parent.

Additionally, as with other important travel documents, one or more original copies of the letter should be kept with the group leader abroad and with a trusted friend or family member in the traveler’s home country.

Please note that failure to provide documentation of parental consent may result in detention of the accompanying adult(s) and minor until the circumstances pertaining to the child’s travel are fully assessed. In some countries (e.g., Canada), entry at the border may be refused. Additional information regarding this topic is available on the U.S. Customs and Border Protection website: Traveling with children - Minors under 18 years of age traveling to another country without their parents and Child traveling with one parent or someone who is not a parent or legal guardian or a group.

2. Passport Minors under the age of 16 cannot apply for a passport by themselves. Rather, both parents/guardians must appear in person with the minor and provide consent, authorizing passport issuance to the minor. If one parent/guardian is unable to appear in person, then the DS-11 application must be accompanied by a signed, notarized Form DS-3053: Statement of Consent from the non-applying parent/guardian. Additional details regarding U.S. Department of State restrictions on issuance of passports to minors are available online: Children Under 16.

3. Visas Depending on the location, minor children may be required to obtain special visas or stay permits.

4. Institutional Approval The USG institution considering minors to participate in study abroad programs might consider the type of program the student is interested in (e.g. Faculty-Led, Exchange, Third Party Provider programs) and make decisions either based on this type of program, or on a case-by-case basis.

If the institution will allow Minors to participate, then the institution should create templates of the following documentation, at a minimum:

- Consent for a Minor Study Abroad Travel and Participation

- Travel Authorization of Minor to Leave US (for airlines, TSA, border agents)

- Consent for Medical Treatment of Minor (for local clinic)

Again, it would be best practice to have the letter of consent signed by both parents and notarized.5. Faculty Training If the institution will allow a Faculty-Led study abroad program to accept Minors, then policies need to be considered and specific trainings should be required of the faculty leaders. These trainings could address how to handle documentation, interactions with on-the-ground providers/arrangements, and/or how the trip fits into any existing ‘Protecting Minors on Campus’ policies.

6. Effect on Program Activities The institution should consider each aspect of the program and how Minor participation would affect the overall trip/organization, the Minors’ experience, and the experience of other non-Minor participants.

The following is a non-inclusive list of questions to help institutions further guide their evaluation when considering the participation of Minors:

- Does the insurance policy cover Minors?

- Since Minors cannot legally sign all agreements and waivers, how will you expand these agreements to include an extra layer of parental consent?

- If the study abroad program is Faculty-Led, will the faculty member need to sign off or agree to any extra layers of guardianship?

- What is the age of consent in the destination country?

- What special preparations will need to be made in advance of the trip?